Tags

1%, Amartya Sen, american economy, Anyway?, Batker, book review, Business books, de Graaf, Federal Reserve Chai Ben Bernanke, Gifford Pinchot, Jeremy Bentham, Joseph Stiglitz, occupy, Publisher's Weekly, What's the Economy for

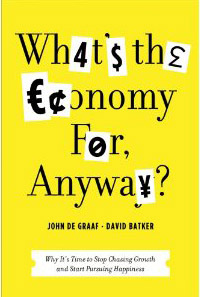

Authors de Graaf and Batker take an unconventional look at how we tie ourselves into knots of anxiety over concepts that add little value to our lives. Their new book What’s the Economy For, Anyway?: Why It’s Time to Stop Chasing Growth and Start Pursuing Happiness dovetails with current Occupy efforts—this is a time to question not only where we are, but how we got here and de Graaf and Batker are up to the challenge—they address themes of consumption, economics and the pursuit of happiness in an America boosting over 14 million unemployed with vast wealth being held by 1% of the population.

What’s the Economy For, Anyway? Why It’s Time to Stop Chasing Growth and Start Pursuing Happiness gives a broad ranging perspective on the history behind Gross National Product and Gross Domestic Product as economic measures, themes of global development and the steady decrease in quality of life ratings for American citizens.

A well-researched tome which pulls insights from economists like Jeremy Bentham, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, Nobel Prize-winning Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen as well as politicians Senator Robert F. Kennedy and French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who contribute policy suggestions that seem essential alongside necessary changes recognized by such strongholds of capitalism as the World Bank. Mix in a bit of John Muir and Michael Moore and here is a cuppa thought brewed from our very own daily grind. de Graaf and Batker’s “What’s the Economy For Anyway?” has been named “Best Business Book for Fall 2011” by Publishers Weekly. de Graaf also was a featured speaker at Bioneers this year.

de Graaf and Batker establish an outline for the solution to America’ economic woes by way of a pamphlet written by Gifford Pinchot in 1905. Pinchot, the first chief of the United States Forest Service was a Republican Yale Graduate, forward thinking perhaps, radical, absolutely not. The pamphlet asserts a systematic approach to the very beginning of forestry and conservation—a way to do the job he had been hired to do, managing the public forests of America. He identified three key ideas, which de Graff and Batker utilize in their proposal for amending not just the economy, but also America’s attitude toward the economy. Pinchot wrote the basis of forest management should be to achieve “the greatest good for the greatest number over the longest run.” This trinity, Pinchot’s mandate, can be seen as “What’s the Economy for, Anyway’?” foundation thesis.

But it is not just attitude and policy that de Graaf and Batker’s book addresses. They take us around the world to see what works where and ask some hard questions about why. Most importantly, the authors build a convincing picture of the United States’ poor report card on quality of life standards and discusses working models and comparative societal traits in detail. For instance, a World Health Organization study done in 2000 ranked the United States 37th in the quality of its health care.

They write, “You might be surprised to know that by 2012, we Americans will be spending nearly $9,000 per person per year on our medical system, almost 18 percent of our whopping GDP. We’re already spending $2.5 trillion a year on health care. Soon, if present trends continue, we’ll be spending one dollar out of every five on health, or rather, sickness, care alone.” Or consider that the United States is one of only a handful of countries that mandate no vacation time at all for workers (alongside Guyana, Suriname, Nepal, and Myanmar).

Faced with a depressed economic climate, the Netherlands developed the Working Hours Adjustment Act, which allows for reduced hours while preserving jobs, benefits, and productive workplaces. This act has led the Netherlands to the world’s highest percentage (46 percent) of part-time workers, with benefits and without the stigma that accompanies part-time workers in the U.S. Germany has adopted a similar law.

What do top countries have in common? According to a 2009 Forbes magazine ranking quoted by de Graaf: “They are highly egalitarian, having among the world’s smallest gaps between rich and poor; they pay great attention to work-life balance, having some of the world’s shortest average working hours; and they pay some of the world’s highest taxes.”

De Graaf and Batker propose many recommendations for moving America forward. Some of the best actions draw on successful models like New Deal-era WPA projects and new approaches employed in European cities. While looking at policy, immediate local adjustments in day to day choices are included, such as time spent engaging with others while walking during shopping at farmers markets and a natural flow of cultural orientation that urban planners, social anthropologists, and economists are increasingly recognizing as significant factors in thriving communities. Jennifer Lail, a University of Washington graduate student quoted in the book, observed the Danish attention to social connection while she was studying in Copenhagen.

“People can stop to rest and chat awhile with friends or strangers. Before I came to Copenhagen, I thought I knew what livability was, but I didn’t.”

De Graaf cultivates a thesis-like structure for his outlook, which is great in terms of organization, building a case and laying out an argument. He is an engaging writer with an unusual perspective, reminding the reader that if, instead of looking straight on, you squint your eyes and cock your head (like a viewer would at those graphics with hidden images), sure enough something new and unexpected pops up. An entire section on solutions concludes the book, leaving this reader to return to earlier discussions. An alternate approach of offering solutions sprinkled more topically could improve accessibility of this highly readable, mind-shifting book.

This is a book for inquiring minds that do not stop asking at the first sign of a question mark and are not afraid to engage openly in an examination of American values.

(See also Seattle talk dates)